More and more reports from Japan describe a disturbing phenomenon: young women traveling overseas not in search of opportunity, education, or adventure, but to sell sex in order to support the hosts they have fallen emotionally and financially captive to. Their journeys, often hidden behind glamorous illusions of romance and quick money, reveal a darker system, one in which affection is weaponized, debt is engineered, and the female body becomes the expendable fuel of a transnational industry.

This black market operates through a tightly sealed loop of cross-border prostitution. Recruitment begins in host clubs, where intermediaries single out women they believe can be persuaded or pressured into compliance. The pitch is simple and enticing: short-term, extremely high earnings abroad. Many are then sent to countries such as Australia or Canada, where their passports are confiscated and a “dorm monitor” restricts their movements. Except for a few hours of sleep, they are forced to receive clients continuously. Although a woman may earn between 10 and 20 million yen in two months, the reality is marked by violence, drug dependence, and accounts of victims returning home covered in bruises.

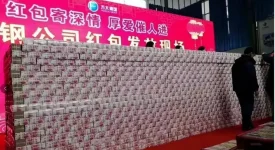

The profits rarely remain with the women themselves. They flow back into the host industry through a system of emotional manipulation. Hosts manufacture the illusion of exclusive affection, cultivating dependence until a woman begins spending heavily to please the man she believes cares for her. When her debts pile up, the host introduces her to a pimp as a “solution”. As much as 90% of her prostitution earnings reportedly return to the host club, funding extravagant champagne towers priced upward of half a million yen and boosting hosts in their competitive rankings. The result is a punishing cycle: prostitution to support the host, which leads to deeper debt, which in turn leads to more prostitution.

Organized crime is deeply embedded in this machinery. Some host clubs maintain exclusive pimping teams and work with overseas prostitution networks, forming a coordinated transnational chain. According to the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department, sophisticated criminal groups even forge travel visas to evade immigration scrutiny, allowing the operation to continue largely unchecked.

This cycle is sustained by broader socioeconomic pressures. Japan’s tax structure penalizes dual income households, reinforcing women’s financial dependence on male partners. 70% of non-regular workers are women, who earn just under three quarters of the average wage of men. In this environment of systemic inequality, hosts exploit loneliness and the desire for emotional connection, offering constant attention through private messaging and installment-based plans that keep women spending.

For many, economic stagnation leaves few alternatives. Social mobility is limited, nearly half of university students carry significant student debt, and some young women enter the adult industry simply to stay afloat. One striking case involved a 24-year-old civil servant who held part-time jobs at eight different sex establishments simultaneously, earning over 8 million yen a year, all to finance her host.

Legal frameworks have failed to keep pace with these evolving exploitation networks. A 2025 revision to Japan’s Adult Entertainment Business Law bans kickback payments to pimps but leaves host clubs untouched. Proposals to punish sex buyers have gained political attention but lack detailed implementation. Meanwhile, non-governmental organizations working with customs officials in Australia, Canada, and the United States attempt to intercept women suspected of being trafficked, but traffickers now label their trips as “cultural exchange”, and victims often hide the truth out of shame.

This crisis also evokes painful historical memories. In the Meiji era, Japan sent more than 140,000 women overseas for prostitution to earn foreign currency, revenue that helped fund major military campaigns. Today’s events are viewed by many as a tragic echo of that history. At the same time, some data remain contested: the widely cited figure that 40% of victims are under 25 comes from NGO estimates rather than official statistics, and the claim that 90% of earnings go back to hosts lacks independent verification.

Despite these uncertainties, the underlying structure is clear. When emotional needs are commodified, when legal systems overlook key perpetrators, and when economic pressures narrow women’s choices, exploitation becomes systemic. Women’s bodies are transformed into consumable resources in a cross-border industry that thrives on vulnerability.

Addressing the problem requires dismantling each link in this chain. Japan must abolish discriminatory tax policies to strengthen women’s economic independence. Authorities must hold host clubs and criminal networks accountable. Just as importantly, psychological support and vocational training programs are needed to break the cycle of emotional dependence and debt that keeps victims trapped.

“Her passport taken, an alarm clock set to call clients, and even after returning home she whispered, ‘That was my host.’” In this tragic black market, the perpetrators extend far beyond pimps or recruiters, they include the societal structures that make such exploitation possible in the first place.