When people start complaining that even Pinduoduo 拼多多 feels “too expensive”, and buying a pair of underwear requires repeated price comparisons, consumption downgrading has clearly moved beyond a personal lifestyle choice and turned into a nationwide survival strategy. Behind it lies a double squeeze: shrinking assets on one side, and a growing sense of rational awakening on the other.

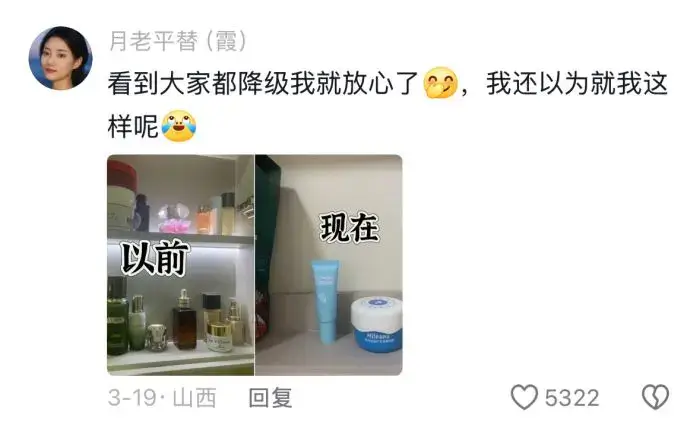

The change is most visible in everyday spending, where habits have shifted almost overnight. Clothing purchases have moved from big name brands to plain, practical items priced around a hundred yuan. International skincare labels are replaced by domestic alternatives, and even a seven yuan cup of milk tea can trigger hesitation. Service consumption has been quietly restructured as well: gym memberships give way to running in public parks, ten yuan haircut booths replace high-end salons, and even small treats like buying a sausage while picking up a child from school are carefully calculated. What once felt casual now requires deliberation.

For big-ticket items, the brakes have been slammed even harder. The property market has cooled sharply, with housing prices in major cities falling by 30 to 40%. For the post-80s and post-90s generations who bought at high prices, this has translated into household wealth losses often exceeding a million yuan. Faced with shrinking balance sheets, families have frozen major purchases and stretched the lifespan of durable goods. Smartphones are kept for five to eight years instead of being upgraded every cycle, and car buyers increasingly favor low-cost electric vehicles, where electricity costs a fraction of fuel. Consumption has not disappeared; it has become slower, more cautious, and far more strategic.

At the root of this shift lies a deep sense of financial insecurity. Falling property values have eroded what many families once saw as their ultimate safety net, while mortgage payments consume close to half of monthly expenditures for some households. Saving has surged. Household deposits reached record highs, and a paradox has emerged: the more people save, the less willing they feel to spend. Income anxiety adds to the pressure. Job discrimination against workers over 35 has intensified, youth unemployment remains elevated, and pay cuts or canceled bonuses are no longer rare. Under such conditions, cutting consumption often feels less like a choice and more like a defensive maneuver.

At the same time, consumption downgrading is not purely about fear. It also reflects a broader disillusionment with consumerism. Shoppers now compare prices across multiple platforms, taking days rather than minutes to make decisions. What used to be about signaling status has shifted toward building resilience. Savings, skill training, and health-related spending are increasingly seen as non-negotiable priorities. Many young people openly admit that the money saved on branded goods is redirected toward courses that improve their employability or long-term prospects.

Some people see this as forced compromise, pointing to middle-class families cutting travel budgets or extracurricular classes under the weight of mortgages and uncertain incomes. Others argue it is a form of active evolution: people may wear a fifty yuan sweater without hesitation, yet willingly spend thousands on a concert ticket that brings genuine joy. Still others describe a K-shaped divergence, where warehouse clubs selling expensive memberships thrive alongside discount stores specializing in nearly-expired food. These realities coexist, revealing not a single path but multiple adaptations to the same economic climate.

High-end dining has suffered, with thousands of upscale restaurants closing in major cities, while affordable essentials and emotionally driven consumption grow against the tide. Budget beverage chains expand rapidly, and premium concert tickets sell out within seconds. The market is splitting into two tracks, rewarding either extreme efficiency or intense emotional value, while squeezing what once sat comfortably in the middle.

Some freeze housing-related ambitions and redirect spending toward experiences like travel, giving rise to the sentiment of “too scared to buy a home, but brave enough to see the sea”. Others chase extreme value, waiting for late-night discounts at supermarkets or circulating unused items on second-hand platforms, where transaction volumes have surged. Yet there is also a growing awareness of red lines: saving money should not come at the cost of skipping medical checkups or buying unsafe, low-quality goods.

In the end, the most striking paradox is this: while luxury boutiques stand empty, free campsites overflow with people. Consumption downgrading, at its core, is less about poverty than about a return to value. People are no longer willing to pay for vanity or inflated symbols of status. They are still willing to spend, but only on what feels real, necessary, and emotionally fulfilling.