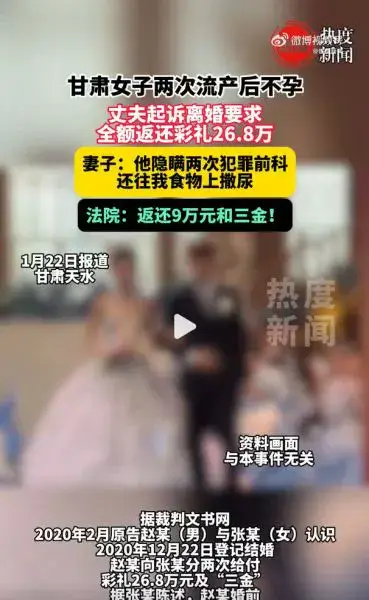

A divorce case from Tianshui, Gansu Province has sparked intense nationwide debate in China over marital responsibility, the true nature of bride price, and the protection of women’s rights. The case centers on a woman who lost part of her uterus during surgery for an ectopic pregnancy and was later sued by her husband for divorce and the return of bride price and jewelry. The court ultimately ruled that she must return 30% of the bride price, amounting to 42,000 yuan, as well as all gold jewelry, a decision that many netizens see as deeply troubling.

According to reported facts, the couple met in 2019 and held a wedding ceremony in 2021. At that time, the man paid a bride price of 120,000 yuan, a meeting gift of 20,000 yuan, and provided gold jewelry. They completed their marriage registration in 2023 and lived together for about two years. In 2022, the woman underwent surgery for an ectopic pregnancy, during which her left fallopian tube and part of her uterus were removed, leaving her permanently infertile. The couple separated in 2024, and in 2025 the husband filed for divorce, demanding the return of the bride price, jewelry, and more than 200,000 yuan in marital transfers.

The court approved the divorce and ordered the woman to return 30% of the total bride price and all gold jewelry, while rejecting the claim for the return of marital transfers on the grounds that they were used for joint living expenses. The judgment cited the Supreme People’s Court’s 2024 rules on bride price disputes, taking into account the length of cohabitation, local customs, and the woman’s health damage. It held that full repayment would be unreasonable, yet still required partial restitution.

This outcome has triggered fierce public controversy. Many critics argue that asking a woman who suffered irreversible bodily harm in marriage to return bride price constitutes a form of “secondary harm”. They condemn the husband’s claim as cold and transactional, accusing him of treating marriage as a fertility deal in which the woman’s value is tied to her ability to bear children. Others, however, believe the ruling already reflects judicial consideration for the woman, noting that two years of shared life inevitably consumed part of the bride price’s value.

Medically, most ectopic pregnancy surgeries only require removal of a fallopian tube; removal of the uterus is a rare complication with a very low incidence rate, yet it results in permanent infertility. Current law does not recognize reproductive damage as an independent category of compensation in divorce cases. Instead, courts can only indirectly “compensate” by reducing the proportion of bride price to be returned. In reality, this often forces women to sell personal belongings, such as jewelry, to meet court orders, adding to their financial and emotional burden. Similar cases elsewhere show a stark mismatch between the severity of bodily harm and the level of compensation.

Some men view the nature of bride price as a form of “fertility guarantee”, believing that if the purpose of having children is not fulfilled, the money should be refunded. Past cases, including those involving abortions, have sometimes reinforced this logic. From the perspective of many women, however, bride price is a symbolic blessing tied to marriage, not a refundable deposit. They argue that women’s invisible contributions during marriage, physical risk, housework, emotional labor, are systematically ignored when disputes are reduced to financial calculations. Some have likened bride price refunds to “applying for a refund after consumption”, a metaphor highlighting the perceived commodification of women’s bodies.

The case has also raised questions regarding gender double standards in marriage. While popular sayings claim that women rarely leave infertile husbands whereas men often leave infertile wives, such figures lack reliable statistical backing. Still, real cases suggest an imbalance in how responsibility is assigned. Allegations of serious fault by husbands, such as concealing criminal records or committing domestic violence, often have little impact on bride price rulings, reinforcing the perception that women bear disproportionate consequences when marriages fail.

In judicial practice, courts have increasingly adopted a graded approach to bride price returns. Very short cohabitations may result in repayment of 70% to 90%, while cases involving pregnancy, childbirth, or miscarriage often see the percentage drop significantly, sometimes to zero. Jewelry given during marriage is usually ordered to be returned, whereas money clearly spent on joint living expenses is not. While this reflects a move toward nuance, many believe it remains insufficient when severe health damage is involved.