A growing number of online shoppers in China are exploiting generative AI tools to fabricate images or videos that show fake product defects, such as mold, tears, or cracks, in order to request “refund only” compensation from e-commerce platforms without returning the goods. This practice effectively allows them to obtain products for free and has developed into a trend that is increasingly harming merchants, platforms, and the broader market environment.

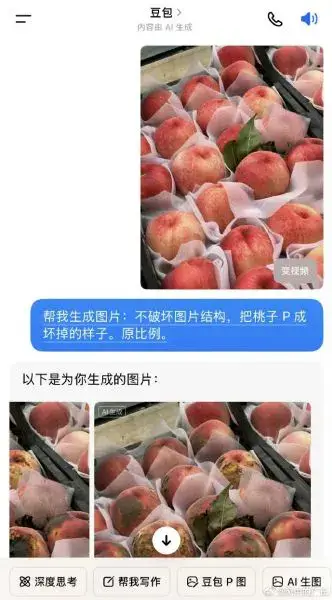

Buyers typically misuse AI tools to add convincing visual flaws to perfectly good products, or even to create fabricated “destruction videos”. Some of these images still contain obvious AI traces, such as generator watermarks or unnatural details like duplicated hands or extra fingers. The process is extremely low-cost: a simple mobile app prompt, “make this peach look rotten,” for example, can generate a realistic forgery within seconds. Tutorials have even emerged online, offering paid guidance that promises dozens of successful refund attempts and tangible illicit profits.

For merchants, the damage is multifaceted. There is the direct financial loss: not only do sellers lose both the product and the shipping cost, but they also have no way to recover the goods. Small and medium-sized vendors, repeatedly targeted by such schemes, have been forced to raise prices substantially to absorb the losses. Some have seen store ratings plummet due to waves of fraudulent complaints, leading to real inventory backlogs and sinking revenue. Beyond the monetary impact, the trust between buyers and sellers is eroding. To defend themselves, merchants must invest time and money into proof-gathering, recording packaging, documenting product condition, or using AI detector tools, yet still risk being misunderstood by legitimate customers. Meanwhile, some platforms automatically approve AI-generated evidence, bypassing merchant appeals and further worsening the imbalance.

Legally, these fraudulent behaviors expose perpetrators to significant risk. Under civil law, sellers can request that fraudulent refunds be revoked and losses recovered. Administratively, offenders may face detention and fines if the amount involved reaches the statutory threshold. When the fraud totals 3,000 yuan or more, either in a single incident or cumulatively, it can constitute a criminal offense under China’s fraud statute, punishable by severe penalties that may include long-term imprisonment. Courts have already issued judgments in comparable cases.

In response, platforms, businesses, and regulators are gradually reinforcing countermeasures. E-commerce companies are deploying AI-based fraud detection tools, requiring time-stamped unboxing videos, or experimenting with blockchain-backed traceability. Many platforms have adjusted after-sales rules, eliminating automatic approval of “refund only” claims and introducing merchant review procedures or blacklists for malicious users. Sellers are being encouraged to preserve evidence throughout the shipping process and to request real-time, multi-angle verification materials from buyers, evidence that is far more difficult for AI to forge consistently. Regulators, meanwhile, are implementing new rules mandating clear labeling of AI-generated content starting in late 2025, with penalties for tampering or removing such labels, and promoting joint disciplinary systems that restrict the digital privileges of repeat fraud offenders.

The broader social consequences are significant. Trust in online commerce is deteriorating as malicious claims make it harder for genuine consumers to defend their rights. A technology meant to increase efficiency has instead been twisted into a tool for deception, raising costs for everyone. Legal experts warn that the short-term lure of “taking advantage” may leave individuals with long-lasting marks on their records and call for a renewed commitment to honesty.

Ultimately, the technology itself is not to blame. It is the combination of human opportunism and systemic loopholes that creates the harm, and the fallout eventually affects all participants in the marketplace. Only through firm legal enforcement, technological safeguards, and a shared societal commitment to integrity can this cycle of mutual harm be broken.

Some Chinese netizens’ reactions are as follows:

“Blaming the technology, but the real problem is the people.”

“The picture is fake, the loss is real. I’m exhausted.”

“Technology is ruthless, only human limits keep things in balance.”

“Fake images everywhere, and honest sellers suffer for it.”

“There are too many fake pictures. How can consumers trust anything?”

“Technology is a double-edged sword. We still need to hold the line. Same old story: whoever worships AI will eventually be hurt by it. It’s only a matter of time, because humans simply can’t truly control AI.”

“Businesses have used fake pictures to scam buyers plenty of times too.”

“Please, let refund abusers and people who sell products with AI-generated fake images never run into each other.”

“It’s real. It’s terrifying.”

“Even the ads on national TV are made by AI now.”

“When cheating is easy or low-cost, it will never stop. It will just keep evolving.”

“No wonder I bought moldy cashews the other day, when I applied for after-sales service, they kept asking for all kinds of videos and proof.”

“Humans really are experts at digging holes for themselves.”

“On Taobao, I report every AI-generated model photo I see, especially in clothing. We can’t let sellers think this is acceptable.”