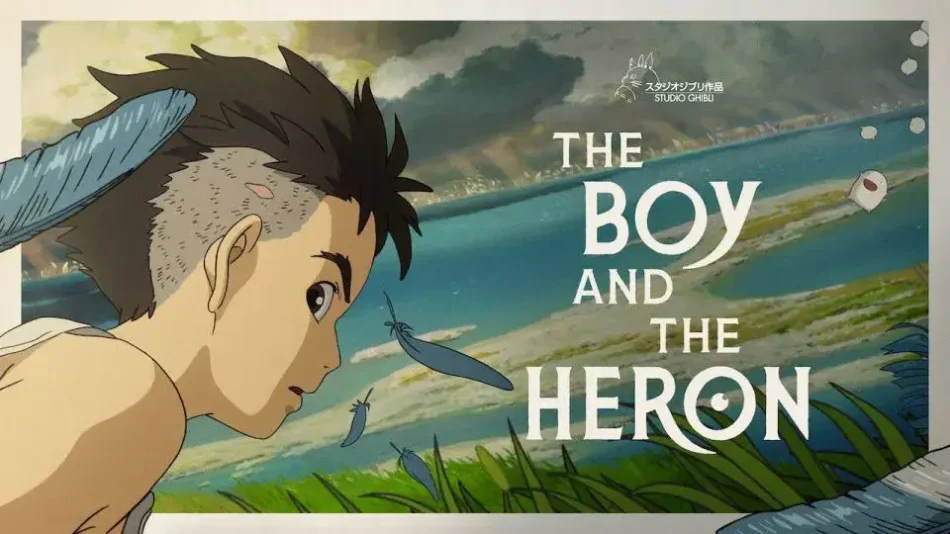

(may contain spoilers)

Douban rating: 7.5

Director: Hayao Miyazaki

Douban Comments: “Since the story is set during World War II, and the protagonist’s family – despite the war – can still get canned food, sugar, and cigarettes thanks to their military factory ties, I really can’t believe there’s no political metaphor in this fantasy world.

A new world built on malice… Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, maybe?

The guide to the other world is a grey heron. In Japanese, ‘heron’ (sagi) sounds the same as ‘fraud’. The pelicans who are tricked into the new world find there’s no fish – just like how settlers lured to Manchuria realized it was nothing like the propaganda promised.

The parrots trapped in the other world represent the army. Eventually, they go berserk and destroy the ‘new world’. But when those same parrots move to a different world, they become gentle again.

It’s not the parrots that were the problem – it was the environment.”

“No wonder there was so little promotion before the release. Compared to commercial animations that cater to the mainstream market, this is clearly a very personal and defiant autobiographical film. At eighty years old, Hayao Miyazaki projects his life experiences into a fictional story, sincerely analyzing himself and sharing the deep insights he’s gained from a life full of ups and downs.

Like most of Studio Ghibli’s films, it uses fantasy and adventure to tell a story of personal growth. Though the expression is obscure and the metaphors are complex, there’s no need to overanalyze every scene. The value lies in savoring and reflecting on it carefully.

As the boy follows the heron into the tower, the audience, too, falls into the creator’s subconscious. This final film feels like a Miyazaki collection. The thirteen blocks represent the thirteen masterpieces of his career, together building the spiritual sanctuary he’s cultivated over the years. The final collapse of the utopia symbolizes farewell, but it also carries Miyazaki’s message to younger generations: a perfect utopia doesn’t exist. In the end, we all have to return to the chaotic, imperfect real world. Avoiding or resisting it is pointless. The true heroism lies in loving life even after recognizing its harsh truths, and in courageously accepting the life you’ve chosen.”

“Indeed, every director who grew up in the Showa era faces the same question in their later years: how to reconcile with the Showa era? The castle built by the great-uncle undoubtedly represents the values of Western democracy and scientific rationality that the Meiji period aspired to – dreams of a wealthy and powerful nation. When this castle is destroyed by militarism, the protagonist doesn’t yearn to rebuild his ideal nation. After witnessing the destruction caused by war, what he truly needs is the healing of freedom. The mother lost in the flames becomes a nightmare, but in the fantasy world, she is reborn from the fire and saves the child’s life. The labyrinth-like adventure, the ambiguous guide, and the temptations faced along the way lead to the final question: transitioning from the grand collective narrative to personal truth and self. This is not the failure of idealism, but the courage to coexist with evil. A land scarred by destruction and sin still endures, and death cannot overcome new life. In this film, we face a calm yet contradictory Miyazaki, but what he has always insisted on is this: the courage to live is not about forgetting painful memories, but about keeping them.”